We were Negro back then. It took me awhile to realize when the TV newsmen spoke of the Negro race, they meant me, my family, and most of the people in my Oakland neighborhood. For the adults, Negro didn't produce the disdain felt for the other N-word. But then there was the variation used mostly by Southern Whites who called us Niggras. We would hear this term when whites were interviewed during the civil rights battles in the South that were going on in the late-fifties and early-sixties.

But for me, Negro reminded me of the young preacher, the civil rights leader always in suits, who talked about the dignity, hopes, and yes -- dreams of the Negro People. We were a People.... one of my earliest remembrances of our differences. They were Americans...we were a People.

Some of my older relatives, including my mother's oldest sister, insisted that we be referred to as colored, not Negro. To her, colored represented 'same as white' with just a little 'color' added in. And indeed, in my family as in most Negro families, there were relatives with very little 'color added in' who passed as white.

My aunt - the colored girl - as black women were referred to back then regardless of age, worked in the homes of wealthy whites on Nob Hill in San Francisco. Every now and then she would take me with her to visit 'Miss whoever-she-was-working-for-at-the-time.' The well-dressed woman was usually some rich man's wife, widow, or mother. The women always seemed nice enough, but I was too young to really understand there was more dividing us than wealth.

To them, I was a cute little colored girl. To me, they were rich white ladies who kept wanting to give me things - candy, clothes, books, cash - they just felt the need to shower me with gifts whenever they saw me. This was okay with me. Mostly, I wasn't allowed to accept gifts from anyone, but with my aunt standing near I learned to graciously acknowledge their kindness toward me. I'm sure lots of little Negro kids learned this routine.

The other whites we interfaced with were the military guys who served with my uncles. They would bring their young white girlfriends to our house. One guy left his girlfriend with us...shipped out and didn't come back to her or their upcoming baby. I believe her name was Maxine and she did what so many of the girls did in that situation. (You see her circumstance was not unique.) She found another sailor and left with him. She did stay in touch with our family for many years however, knowing that she would have been out on the streets without us.)

In 1960, there were a few lower-income whites that couldn't escape our mostly Negro neighborhood. I went to school with their offspring at Grant Elementary (since torn down) not far from our 28th and Telegraph apartment. My best friend in Kindergarten was a white kid named Jim. For awhile, Jim and I didn't understand the divisions between white and Negro. We needed assistance from our parents.

Mommy, "Whats a nig-a-ro?" I asked one day after school. (My mom still tells this story.) You see Jim had told me his mom did not want us to be friends, and I would not be visiting his house because I was a "nig-a-ro." The friendship was over and shortly thereafter Jim moved away - probably to an area where he didn't have to attend school with "nig-a-ro" kids.

This was race relations for me as a Negro child living in Oakland, California in the early 1960's. This was the backdrop when John Kennedy was running for President and decided to make a campaign swing through Oakland. Even though it was widely known he hailed from a rich family, Kennedy was seen as a champion of the underdog and the Negro People in particular. Like the rich white ladies on Nob Hill, surely he had many gifts to offer us.

There was quite a commotion surrounding Kennedy's visit to working-class Oakland. Since Grant Elementary was near the route he would take on his way to de Fremery Park to greet supporters, it was decided that students would witness his visit first-hand -- lining the streets of his route to the park. I was happy because I was selected to wave the flag for my class as he drove by.

There was quite a commotion surrounding Kennedy's visit to working-class Oakland. Since Grant Elementary was near the route he would take on his way to de Fremery Park to greet supporters, it was decided that students would witness his visit first-hand -- lining the streets of his route to the park. I was happy because I was selected to wave the flag for my class as he drove by.

On November 2, 1960 Kennedy's motorcade (I didn't know it was called that until three years later) whizzed by and being small I didn't see a thing. I just heard them say, "Wave the flag, Linnie...Wave the flag!" And I did so (even though it was heavy) with all my might. I kept waving that flag until they told me to stop. Kennedy was probably miles away by then. They say Kennedy was mobbed by supporters at de Fremery Park and needed a police escort to get away.

Most of the Negros and the Colored People in my community loved John F. Kennedy and they were ecstatic when he won the Presidency the following week.

On November 22, 1963, I was in third grade at Brookfield Elementary School in what is called East Oakland. During recess we played tag almost every day. (Around that age the kids still played tag....normally the boys chasing the girls, however now I think the girls do some chasing of their own.)

We stopped our running and hiding when we noticed our teacher Mrs. Doxey, and some of the other teachers, crying and looking stunned. Mrs. Doxey brought us back into the classroom and told us the President had been shot. Not long after, I looked up and saw my mother at the door. She had come to get me. We only lived a few blocks from the school and she had walked over. She was the room mother so Mrs. Doxey knew her. In those days, all it took was a nod and I was released to go home with my mom.

There was sadness in our home and in the neighborhood when the President died. An overwhelming grief I had never seen - even when we had lost family members and friends. People who had suffered many hardships felt this was one more blow - it was personal.

The adults didn't spend a lot of time discussing conspiracy theories, since the majority of them were from the South and understood not getting answers on the murders of loved ones. They did however attribute the murder to Kennedy's stand on civil rights for the Negro People. Perhaps it made them more determined to fight.

|

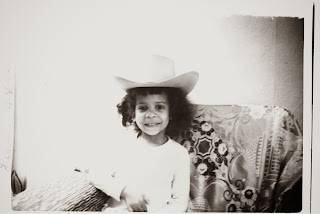

| 1960. Me and my cowboy hat. |

My family was from Dallas and had always been proud of their Texas culture. I had cowboy hats and boots from the time I was born. Suddenly, Dallas wasn't so popular anymore and the hats and boots were put away for years.

They say you never forget where you were or what you were doing when you hear the news of something like the Kennedy Assassination (or recently 9-11). At the time, we did not know if Kennedy's death marked the end of the civil rights battle, or if it would continue.

They say America lost its innocence on November 22, 1963. Nevertheless, there was also the coming together of a people united in grief. We came together not as ethnic groups, but as Americans.